You Speak, I Listen

By the time the sketch for this novel went from my head to words on a page, I was already clutching the characters to my chest, holding them and all their troubles tight. They were mine, I thought, but really, I was theirs. All theirs. If I didn’t give them enough time to figure things out, if there was one false note to a conversation, if I glossed over a detail or underestimated their terror or vitality, they gnashed their teeth and rolled their eyes, like the wild things in Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. The only way I could face them day after day was to approach each one with love and rigor, to let them know that nobody was leaving until we got it exactly right.

Some days the words got stuck like behind a dam and a character would step forward to help me break through, stone by stone. Other days the words spilled out in every direction and it was a race to catch them. The trajectory was never straight—homecoming never is—but it was dogged and true.

For me, there is no going back to Iran, but word by word, my characters clawed their way there to find out what it means to be home, to explore the questions of identity and belonging. I learned that writing a novel is a vow between the writer and the reader, not unlike the unspoken promise between a doctor and his patient, or a chef and his diner. Listening is important, and there might be a need to show some technique. But no less vital is a commitment to detail, a desire to imagine what it is that another feels or thinks. Otherwise, the reader will not be moved, the patient will not be cured, and everyone will go to bed without supper.

A Kitchen Drawer

My mother wrote her recipes in prose, linking ingredients together into homespun expressions, putting you at ease, making it seem as effortless as boiling an egg: “Just add a handful of sugar to a pot of cherries and cook them until they stop bobbing to the surface.” These cherries were later folded into saffron rice with slivered almonds and orange peel, but never mind that now, the cherries are tiny and take a while to pit – a task we’ll share over a cup of tea. So that’s how I learned to cook Persian food, by knowing a handful could mean a half a cup or more, that only lazy cooks don’t bother to pit stone fruit before cooking it, and patience is an essential ingredient.

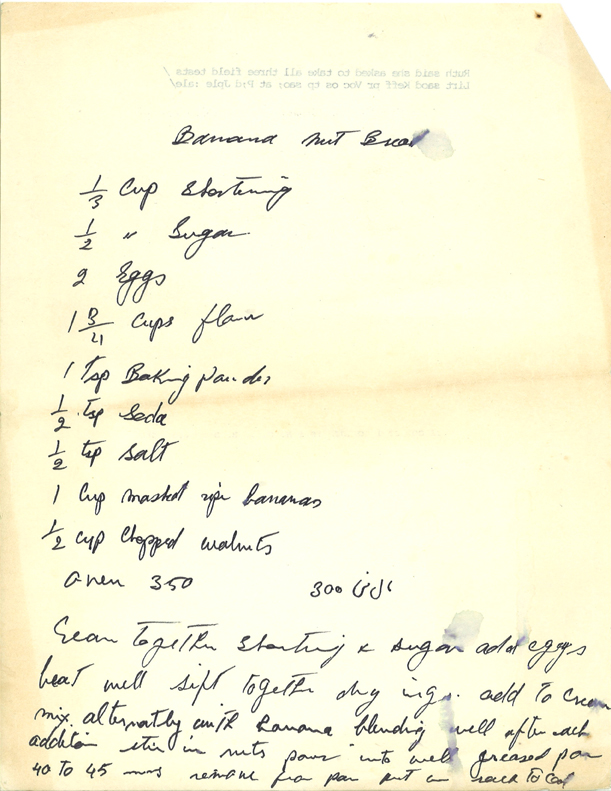

I should not have been surprised then, to find a drawer brimming with recipes in her long hand on paper ripped from bank deposit slips and prescription pads, some in Farsi, some in English, and written like words of advice versus formulas. But on that afternoon, just days after she died, I felt compelled to dismantle her kitchen, lining up boxes like little coffins and filling them with cups and saucers. When I pulled open a drawer, I didn’t expect to find a dozen variations of tuna casserole, macaroni and cheese, and banana bread – a compilation of American dishes she had made great efforts to master. I put all the recipes in a manila file tied with string and brought them home. They sat on my bookshelf for a year before I could bear to look at them again. But I thought about them every day like solving an equation backwards, trying to understand how I had come upon the result. My mother, a woman well versed in Persian cookery, was taking notes on the multiple ways to make coleslaw. There was Jenny’s version with shredded apples, and a

restaurant version with whole grain mustard. In Pat’s oatmeal raisin cookies, she had overruled her neighbor’s attempt at precise measurements and written loose instructions to give herself plenty of room to make mistakes. I think it was her way of making it her own. Amassed haphazardly over the course of twenty five years, since her immigration to America in 1980, these handwritten recipes were a testament to her diligent efforts to assimilate, expand her repertoire, and teach herself American cookery.

In my efforts to understand what happens to those left behind and how to cope with loss, my first instinct was simply to write my parent’s story – a doctor and a nurse who escaped execution and took refuge in America. I soon realized that the only story I could write, other than an anecdotal account of their lives, was my story: my experience as their daughter, how I was shaped as an Iranian-American, and the role I played within the family unit as a link between two cultures. A persistent feeling occupied my thoughts that I had not appreciated my mother’s tenacity, her will to piece together a new life in an unfamiliar land, to recreate a sense of place for her children, and foster friendships and love for their adopted country. They say that survivors look for messages. I saw her collection of recipes as an incentive to understand her experience in exile, following our path as we made our way to America while looking over my shoulder at what we left behind.

In my family food was the language we used to tell stories, to communicate love, share our passions, and our values. I am intrigued by the fact that a country can be ravaged by fundamentalism and war, its citizens scattered like shards of glass over the globe, and yet its food remains intact. Food allows us to hold on to something sensory, providing not only nourishment, but security, dignity, and love. In writing this book I have followed a yearning certainly for comfort and solace, but also to unravel the interior world that all immigrants inhabit. My mother looked in between cultures to find meaning, to understand how we are all connected in a world of appetites. She wrote recipes like stories, knowing instructions are not compelling, but hunger is.

Tea with Ghosts

My Uncle Darius died a few days ago. He had a stroke and collapsed in his home, alone. He had stayed behind in Tehran while my aunt went to Canada to visit their children and grandchildren. In better years, they may have lived beneath the same roof or at least in the same town but we, their children, their nieces and nephews, are the seeds that were scattered abroad to save us from tyranny.

The last time I saw my uncle was on a brief visit to Iran after 32 years in exile. I returned fatherless, motherless, middle-aged, a stranger. Yet he took me in his arms like the fifteen-year-old niece he’d last seen in 1978. What shook me to the core was his voice. He was my father’s baby brother, their voices parroted one another, so when he said my name, my pet name, Dony joon, my heart burst. He looked smaller than I remembered him being. He had my father’s beak nose and I could not take my eyes off of it. My dad died in 1997 but what mysterious heirlooms he imprinted on this man, of whom I was so fond, sitting beside me drinking tea, his nose obstructing the path of a teacup to his lips. He spoke with the same emphasis on certain vowels, the endearing accent of northern Iran—my father advising me. When his wife interrupted him, he made a face “Let me finish!” Yes, let him, I thought. How I wanted to reach out and touch his nose, to capture the words that tumbled from his mouth into a Mason jar, to later hold the glass like a seashell to my ear when I missed my dad.

I returned home to California but I could not forget that close encounter, that feeling of holding something so dear. Dony joon echoed in my ears. What solace there was in knowing that so vital a piece of my father, his voice, still lived inside my uncle.

Growing up, these two brothers remained close, they married and filled their houses with children and then emptied them when one was forced to leave with his family and one chose to stay and send his children abroad. One is buried in a cemetery in California and one was buried today, in Tehran. The world has gone mad, lives vandalized, families ripped apart, fathers die alone, sons and daughters adrift. We try to make our parents proud, we strive, sometimes we succeed, we assimilate, we raise children who may never know their grandparents, and rarely do we mother our mothers, or nurse them when they become ill. One April afternoon, the awful news travels across telephone lines while I’m at my child’s track meet. All in a moment, the pendulum swings back to the street where I grew up. I know exactly where he fell. I know how the telephone rings in that house. I know the sound of that buzzer, unanswered. I know all this from seven thousand miles away.

My aunt flew home on the first flight. Home, what home? Without a husband, without children and grandchildren, it’s a widow’s lair where the survivor returns to seek her mate in a coat still on a hook by the door, his watch on the chest of drawers, a morning teacup in the sink. She will put the kettle on. She will sit at the kitchen table to drink her tea, bitter and sweet, and she will bide her time until one day her children call her West. And so there will be no trace of anyone’s life in that house, no pictures, no linens, no teacups, no voices of our fathers. She would never come back.

So many of us will face Father’s Day without our fathers. Not all of them are gone from this world. Not yet. Some are unable to cross a border to reach their families, some lay in hospice, some are estranged. After all, what is our duty to our fathers? Is it to arrive in time to say goodbye? Is it to call on Sunday afternoons? To remember a birthday or that he gave up ties, his hands too shaky to make the knot? Is it to follow in his footsteps? To be patient with our children when they’re learning to tie their shoelaces or drive a car? Or is it simply to listen for that embedded voice? The voice of caution, the voice of wisdom, and of love, reassuring us that we were cherished, sometimes imperfectly, but cherished.